Please contact our Webmaster with questions or comments.

© Copyright 2002-2022 Barry P. Foley. All rights reserved.

From Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tulsa_race_massacre

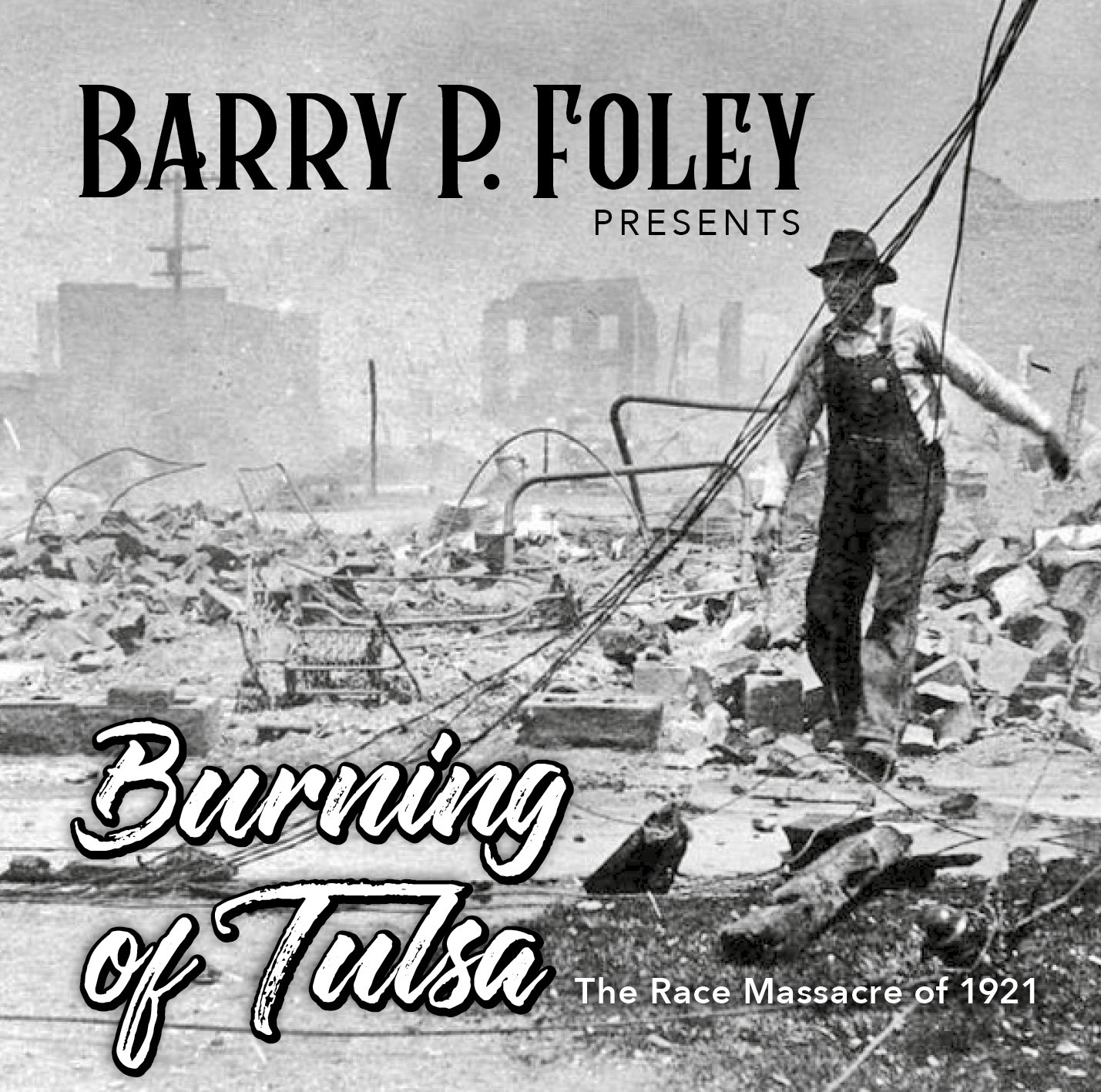

Tulsa Race Massacre 31 May - 01 June 1921

The Tulsa race massacre took place on May 31 and June 1, 1921, when mobs of white residents, some of whom had been deputized and given weapons by city officials, attacked Black residents and destroyed homes and businesses of the Greenwood District in Tulsa, Oklahoma, US. Alternatively known as the Tulsa pogrom, the Tulsa race riot or the Black Wall Street massacre, the event is considered one of "the single worst incident[s] of racial violence in American history". The attackers burned and destroyed more than 35 square blocks of the neighborhood – at the time one of the wealthiest Black communities in the United States, known as "Black Wall Street". More than 800 people were admitted to hospitals, and as many as 6,000 Black residents of Tulsa were interned in large facilities, many of them for several days.

The massacre began during the Memorial Day weekend after 19-year-old Dick Rowland, a Black shoeshiner, was accused of assaulting Sarah Page, the 17-year-old white elevator operator in the nearby Drexel Building. He was taken into custody..Upon hearing reports that a mob of hundreds of white men had gathered around the jail where Rowland was being held, a group of 75 Black men, some of whom were armed, arrived at the jail in order to ensure that Rowland would not be lynched. The sheriff persuaded the group to leave the jail, assuring them that he had the situation under control. An elderly white man approached O.B. Mann, a Black man, and demanded that he hand over his pistol. Mann refused, and the old man attempted to disarm him. Mann shot him, and then, according to the sheriff's reports, "all hell broke loose." At the end of the exchange of gunfire, 12 people were dead, 10 White and two Black. Subsequently the militants fled back into Greenwood shooting as they went. As news of the violence spread throughout the city, mob violence exploded. White rioters invaded Greenwood that night and the next morning, killing men and burning and looting stores and homes. Around noon on June 1, the Oklahoma National Guard imposed martial law, ending the massacre.

About 10,000 Black people were left homeless, and property damage amounted to more than $1.5 million in real estate and $750,000 in personal property (equivalent to $32.65 million in 2020). Many survivors left Tulsa, while Black and white residents who stayed in the city largely kept silent about the terror, violence, and resulting losses for decades. The massacre was largely omitted from local, state, and national histories.

Many servicemen returned to Tulsa following the end of the First World War in 1918, and as they tried to re-enter the labor force, social tensions and anti-Black sentiment both increased in cities where job competition was fierce. Since 1915, the Ku Klux Klan had been growing in urban chapters across the country. Its first significant appearance in Oklahoma occurred on August 12, 1921.] By the end of 1921, 3,200 of Tulsa's 72,000 residents were Klan members according to one estimate. In the early 20th century, lynchings were common in Oklahoma as part of a continuing effort to assert and maintain white supremacy. By 1921, at least 31 people, mostly men and boys, had been lynched in the newly formed state; 26 were Black.

At the same time, Black veterans pushed to have their civil rights enforced, believing that they had earned full citizenship as the result of their military service. In what became known as the "Red Summer" of 1919, industrial cities across the Midwest and Northeast experienced severe race riots in which Whites attacked Black communities, sometimes with the assistance of local authorities. In Chicago and some other cities, Blacks defended themselves with force for the first time but they were often outnumbered.

As a booming oil city, Tulsa also supported a large number of affluent, educated and professional African-American people. Greenwood was a district in Tulsa that was organized in 1906 following Booker T. Washington's 1905 tour of Arkansas, Indian Territory and Oklahoma. It was a namesake of the Greenwood District which Washington had established as his own district in Tuskegee, Alabama, five years earlier. Greenwood became so prosperous that it came to be known as "the Negro Wall Street" (now commonly referred to as "the Black Wall Street").Most Black people lived together in the district. Black Americans had created their own businesses and services in this enclave, including several grocers, two newspapers, two movie theaters, nightclubs, and numerous churches. Black professionals, including doctors, dentists, lawyers, and clergy, served their peers. During his trip to Tulsa in 1905, Washington encouraged the co-operation, economic independence and excellence being demonstrated there. Greenwood residents selected their own leaders and raised capital there to support economic growth. In the surrounding areas of northeastern Oklahoma, they also enjoyed relative prosperity and participated in the oil boom.

Monday, May 30 (Memorial Day) Encounter in the elevator

On May 30, 1921, 19-year-old Dick Rowland, a Black shoeshiner who was employed at a Main Street shine parlor, entered the only elevator in the nearby Drexel Building at 319 South Main Street in order to use the top-floor 'colored' restroom, which his employer had arranged for use by his Black employees. There, he encountered Sarah Page, the 17-year-old white elevator operator who was on duty. Whether—and to what extent—Dick Rowland and Sarah Page knew each other has long been a matter of speculation. The two likely knew each other at least by sight because Rowland would have regularly ridden in Page’s elevator on his way to and from the restroom. Others have speculated that the pair might have been interracial lovers, a dangerous and perhaps a deadly contemporary taboo. A clerk at Renberg's, a clothing store on the first floor of the Drexel, heard what sounded like a woman's scream and saw a young Black man rushing from the building. The clerk went to the elevator and found Page in a distraught state. Thinking that she had been sexually assaulted, he summoned the authorities. Apart from the clerk's interpretation that Rowland had attempted to rape Page, many explanations have been given for the incident, with the most common explanation being that Dick Rowland tripped as he got onto the elevator and, as he tried to catch his fall, he grabbed onto the arm of Sarah Page, who then screamed. Others suggested that Rowland and Page had a lover’s quarrel.

Brief investigation

Although the police questioned Page, no written account of her statement has been found, but apparently, she told the police that Rowland had grabbed her arm and nothing more, and would not press charges. However, the police determined that what happened between the two teenagers was something less than an assault. The authorities conducted a low-key investigation rather than launching a man-hunt for her alleged assailant. Regardless of whether assault had occurred, Rowland had reason to be fearful. African American men accused of raping white women were often prime targets for lynch mobs. Realizing the gravity of the situation, Rowland fled to his mother's house in the Greenwood neighborhood.

A suspect is arrested

On the morning after the incident, Henry Carmichael, a white detective, and Henry C. Pack, a Black patrolman, located Rowland on Greenwood Avenue and detained him. Pack was one of two Black officers on the city's police force, which included about 45 officers. Rowland was initially taken to the Tulsa city jail at the corner of First Street and Main Street. Late that day, Police Commissioner J. M. Adkison said he had received an anonymous telephone call threatening Rowland's life. He ordered Rowland transferred to the more secure jail on the top floor of the Tulsa County Courthouse.

Rowland was well known among attorneys and other legal professionals within the city, many of whom knew him through his work as a shoeshiner. Some witnesses later recounted hearing several attorneys defend Rowland in their conversations with one another. One of the men said, "Why, I know that boy, and have known him a good while. That's not in him."

Newspaper coverage

The Tulsa Tribune, owned, published, and edited by Richard Lloyd Jones, and one of two white-owned papers which were published in Tulsa, broke the story in that afternoon's edition with the headline: "Nab Negro for Attacking Girl In an Elevator," describing the alleged incident. According to some witnesses, the same edition of the Tribune included an editorial warning of a potential lynching of Rowland, titled "To Lynch Negro Tonight." The paper was known at the time to have a "sensationalist" style of news writing. All original copies of that issue of the paper have apparently been destroyed, and the relevant page is missing from the microfilm copy. The Tulsa Race Riot Commission in 1997 offered a reward for a copy of the editorial, which went unclaimed. Other newspapers of the time like The Black Dispatch and the Tulsa World did not call attention to any such editorial after the event. So the exact content of the column – and whether it existed at all – remains in dispute. However, Chief of Detectives James Patton attributed the cause of the riots entirely to the newspaper account and stated, "If the facts in the story as told the police had only been printed I do not think there would have been any riot whatsoever."

Stand-off at the courthouse

The afternoon edition of the Tribune hit the streets shortly after 3 p.m., and soon news spread of a potential lynching. By 4 p.m., local authorities were on alert. white residents began congregating at and near the Tulsa County Courthouse. By sunset around 7:30 p.m., the several hundred white residents assembled outside the courthouse appeared to have the makings of a lynch mob. Willard M. McCullough, the newly-elected sheriff of Tulsa County, was determined to avoid events such as the 1920 lynching of white murder suspect Roy Belton in Tulsa, which had occurred during the term of his predecessor. The sheriff took steps to ensure the safety of Rowland. McCullough organized his deputies into a defensive formation around Rowland, who was terrified. The Guthrie Daily Leader reported that Rowland had been taken to the county jail before crowds started to gather. The sheriff positioned six of his men, armed with rifles and shotguns, on the roof of the courthouse. He disabled the building's elevator and had his remaining men barricade themselves at the top of the stairs with orders to shoot any intruders on sight. The sheriff went outside and tried to talk the crowd into going home but to no avail. According to an account by Scott Ellsworth, the sheriff was "hooted down". At about 8:20 p.m., three white men entered the courthouse, demanding that Rowland be turned over to them. Although vastly outnumbered by the growing crowd out on the street, Sheriff McCullough turned the men away.

A few blocks away on Greenwood Avenue, members of the Black community gathered to discuss the situation at Gurley's Hotel. Given the recent lynching of Belton, a white man accused of murder, they believed that Rowland was greatly at risk. Many Black residents were determined to prevent the crowd from lynching Rowland, but they were divided about tactics. Young World War I veterans prepared for a battle by collecting guns and ammunition. Older, more prosperous men feared a destructive confrontation that likely would cost them dearly. O. W. Gurley stated that he had tried to convince the men that there would be no lynching, but the crowd responded that Sheriff McCullough had personally told them their presence was required. About 9:30 p.m., a group of approximately 50–60 Black men, armed with rifles and shotguns, arrived at the jail to support the sheriff and his deputies in defending Rowland from the mob. Corroborated by ten witnesses, attorney James Luther submitted to the grand jury that they were following the orders of Sheriff McCullough who publicly denied he gave any orders:

Taking up arms

Having seen the armed Black men, some of the more than 1,000 Whites who had been at the courthouse went home for their own guns. Others headed for the National Guard armory at the corner of Sixth Street and Norfolk Avenue, where they planned to arm themselves. The armory contained a supply of small arms and ammunition. Major James Bell of the 180th Infantry Regiment learned of the mounting situation downtown and the possibility of a break-in, and he consequently took measures to prevent. He called the commanders of the three National Guard units in Tulsa, who ordered all the Guard members to put on their uniforms and report quickly to the armory. When a group of Whites arrived and began pulling at the grating over a window, Bell went outside to confront the crowd of 300 to 400 men. Bell told them that the Guard members inside were armed and prepared to shoot anyone who tried to enter. After this show of force, the crowd withdrew from the armory.

Wednesday, June 1

Throughout the early morning hours, groups of armed white and Black people squared off in gunfights. The fighting was concentrated along sections of the Frisco tracks, a dividing line between the Black and white commercial districts. A rumor circulated that more Black people were coming by train from Muskogee to help with an invasion of Tulsa. At one point, passengers on an incoming train were forced to take cover on the floor of the train cars, as they had arrived in the midst of crossfire, with the train taking hits on both sides. Small groups of Whites made brief forays by car into Greenwood, indiscriminately firing into businesses and residences. They often received return fire. Meanwhile, white rioters threw lighted oil rags into several buildings along Archer Street, igniting them.

Fires begin

At around 1 a.m., the white mob began setting fires, mainly in businesses on commercial Archer Street at the southern edge of the Greenwood district. As news traveled among Greenwood residents in the early morning hours, many began to take up arms in defense of their neighborhood, while others began a mass exodus from the city. Throughout the night both sides continued fighting, sometimes only sporadically. As crews from the Tulsa Fire Department arrived to put out fires, they were turned away at gunpoint. Tulsa founder and Ku Klux Klan member W. Tate Brady participated in the riot as a night watchman.

Daybreak

Upon sunrise, around 5 a.m., a train whistle sounded. Some rioters believed this sound to be a signal for the rioters to launch an all-out assault on Greenwood. A white man stepped out from behind the Frisco depot and was fatally shot by a sniper in Greenwood. Crowds of rioters poured from their shelter, on foot and by car, into the streets of the Black neighborhood. Five white men in a car led the charge but were killed by a fusillade of gunfire before they had travelled one block.

Overwhelmed by the sheer number of white attackers, the Black residents retreated north on Greenwood Avenue to the edge of town. Chaos ensued as terrified residents fled. The rioters shot indiscriminately and killed many residents along the way. Splitting into small groups, they began breaking into houses and buildings, looting. Several residents later testified the rioters broke into occupied homes and ordered the residents out to the street, where they could be driven or forced to walk to detention centers. A rumor spread among the rioters that the new Mount Zion Baptist Church was being used as a fortress and armory. Purportedly twenty caskets full of rifles had been delivered to the church, though no evidence was found.

Attack by air

Numerous eyewitnesses described airplanes carrying white assailants, who fired rifles and dropped firebombs on buildings, homes, and fleeing families. The privately owned aircraft had been dispatched from the nearby Curtiss-Southwest Field outside Tulsa. Law enforcement officials later said that the planes were to provide reconnaissance and protect against a "Negro uprising". Law enforcement personnel were thought to be aboard at least some flights. Eyewitness accounts, such as testimony from the survivors during Commission hearings and a manuscript by eyewitness and attorney Buck Colbert Franklin, discovered in 2015, said that on the morning of June 1, at least "a dozen or more" planes circled the neighborhood and dropped "burning turpentine balls" on an office building, a hotel, a filling station and multiple other buildings. Men also fired rifles at Black residents, gunning them down in the street.

Franklin's account

In 2015, a previously unknown written eyewitness account of the events of May 31, 1921, was discovered and subsequently obtained by the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. The 10-page typewritten letter was authored by Buck Colbert Franklin, noted Oklahoma attorney and father of John Hope Franklin.

“Lurid flames roared and belched and licked their forked tongues into the air. Smoke ascended the sky in thick, black volumes and amid it all, the planes – now a dozen or more in number – still hummed and darted here and there with the agility of natural birds of the air. Planes circling in midair: They grew in number and hummed, darted and dipped low. I could hear something like hail falling upon the top of my office building. Down East Archer, I saw the old Mid-Way hotel on fire, burning from its top, and then another and another and another building began to burn from their top. The sidewalks were literally covered with burning turpentine balls. I knew all too well where they came from, and I knew all too well why every burning building first caught fire from the top.”

Franklin states that every time he saw a white man shot, he "felt happy" and he "swelled with pride and hope for the race." Franklin reports seeing multiple machine guns firing at night and hearing "thousands and thousands of guns" being fired simultaneously from all directions. He states that he was arrested by "a thousand boys, it seemed,...firing their guns every stety took."